ABSTRACT:

The article critically examines Bahareh Hedayat’s open letter from Evin prison written in December 2022. The letter reveals a paradigm shift with respect to the so-called reformist movement – from working within the confines of a theocratic state to calling for its complete overthrow by revolutionary means. This welcome change is a reflection of the secular and anti-clerical revolution unfolding in Iran, sparked by the murder of Mahsa Jina Amini and led by women – a revolution that is convincing many, like Hedayat, that the only solution is revolution. In fact, the whole idea behind the reformist movement was wrong from the beginning: how does one reform God’s laws that are meant to be infallible? Can the rights of women be met within a system of sex apartheid? Can the unreformable be reformed? As for the future of Iran, this is the time to dream big and recognise the vast potential of this revolution to fundamentally change the face of the country and the world by establishing – why not? – a more interventionist direct democracy, such as that being experimented in Rojava.

Bahareh Hedayat (born 1980) is an activist who has been imprisoned multiple times. In October 2022, she was re-arrested amidst the Mahsa Jina Amini revolution and jailed in Evin Prison. She has currently been moved to hospital due to deterioration of her health as a result of a hunger strike.

In December 2022, two months after the start of the Mahsa Jina Amini revolution, Hedayat penned an open letter from Evin Prison. [Political prisoners in Iran have smuggled open letters for years now, including labour activist Sepideh Qoliyan, who recently wrote: ‘The echoes of “Woman, Life, Freedom” can be heard even through the thick walls of Evin prison.’ Upon release in March 2023 after nearly 6 years in prison, Qoliyan shouted ‘Khamenei the tyrant; we will bury you.’ She was promptly rearrested and is back at Evin Prison.]

Hedayat’s letter is entitled ‘Revolution is Inevitable.’

The letter reveals a paradigm shift: from working within the confines of a theocratic state to calling for its complete overthrow by revolutionary means.

Hedayat is best known for her work in the Campaign for Equality which aimed at raising one million signatures to reform the discriminatory laws in Iran and for her support of the Green Movement of the so-called Islamic reformists. She has also been Spokesperson for the Women’s Commission of Daftareh Tahkheem Vahdat(Office to Foster Unity or Office for Strengthening Unity), a government-affiliated student group aimed at organising students ‘within the framework of the constitution and the Islamic revolution.’

This welcome change is a reflection of the women’s revolution unfolding in Iran, sparked by the murder of Mahsa Jina Amini for ‘improper veiling’ on 16 September 2022. This modern, secular, anti-clerical and even anti-religious revolution is led by a Generation Z that has no illusions towards any aspect of the Islamic state. And it is convincing many, like Hedayat, that the only solution is revolution.

In her open letter, she writes: ‘the youth of today’s Iran brought their political demands to the streets and defined them around the slogan of “woman, life, freedom” and the concept of the overthrow [of the Islamic Republic].’ She says the movement is ‘free from the shrapnel of political Islam.’ She adds, ‘In order to explain what it wants and does not want, this generation of protestors has not resorted to any concept that has a religious or even quasi-religious pedigree, and this is a great accomplishment.’

Crucially, she recognises that support for the so-called reformists has been a mistake. At the height of this movement, many of us on the Left did warn that the reformist faction from within the ruling elite was a strategy to maintain the Islamic system with empty promises of illusory reform in the face of widespread opposition from various sectors of Iranian society. After all, the so-called reformists have always been part and parcel of the system. Only men who have shown complete loyalty to the Islamic system have had any chance of entering and remaining in positions of power. They can only run in the farcical elections if approved by Ayatollah Khamenei, the Supreme Spiritual Leader, and the Council of Guardians. And the track records of these ‘reformists’ speak for themselves.

Mohammad Khatami, the ‘leading reformer,’ for example, has been a representative in the Islamic Assembly during the 1980s, Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance responsible for censorship, and a member of the Supreme Council of Cultural Revolution, which aims to ensure that the education and culture of Iran ‘remains 100% Islamic’ as Ayatollah Khomeini has directed.

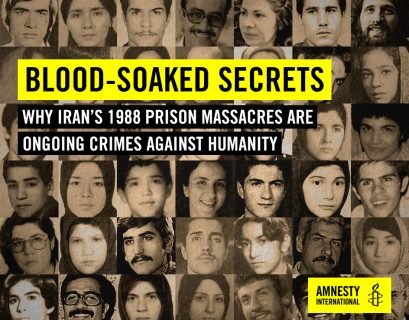

The Green movement leader, Mir Hossein Mousavi, has been a former prime minister during 1981-1989, a period known as the Bloody Decade. In August 1988 alone, in a second wave of mass executions after brief ‘trials,’ thousands who responded negatively to questions such as ‘Are you a Muslim?’, ‘Do you believe in Allah?’, ‘Is the Holy Qur’an the Word of Allah?’, ‘Do you accept the Holy Muhammad to be the Seal of the Prophets?’, ‘Do you fast during Ramadan?’, ‘Do you pray and read the Holy Qur’an?’ have been summarily executed. So why Hedayat’s misguided feelings of betrayal to hear Mir Hossein Mousavi call Ayatollah Khomeini, a ‘vigilant spirit?’

Certainly, the ‘reformists’ have been persecuted, their government-affiliated papers shut down, their candidates barred from running in the ‘elections.’ But hasn’t this regime been built on the suppression and persecution of countless generations? Isn’t it a totalitarian state without free press, speech or thought? Does persecution only matter when those working within the confines of the regime are persecuted? What about all the other bodies buried in mass graves, like in Khavaran?

The earnest use of the term reformist within this widespread repression is repulsive. Reform means real changes in the law that improves the condition of citizens. How does one reform God’s laws that are meant to be infallible? And how can a theocracy that represents God’s rule on earth be reformed? The very idea is considered blasphemous and heretical by theocrats, including so-called reformists that have not only been ‘contaminated with political Islam’ but part and parcel of Islamist rule in Iran for four decades.

The Worker-communist Mansoor Hekmat has said it well in describing a conference in Berlin in 2000 that had aimed to present the ‘reformists’ image of a different Islamic Republic ‘…full of smiles and chirping birds, where harmless mullahs with radiant faces and sheer robes frolic, hand in hand in meadows chasing butterflies, collecting stamps and learning the Internet… [in order to] conceal – behind a cardboard image of a reactionary mullah and worthless utterances about “modern Islam” – the mass executions and stonings, the unmarked graves, the unpaid workers, right-less women, hopeless youth, ruined children, suppressed beliefs and silenced voices.’ The so-called reformists tried to save their regime and failed. The Jina revolution is testament to that.

Hedayat now recognises that people’s demands cannot be met within this structure. Of course, it cannot. Any aspect of an Islamic state, however presented and packaged, is antithetical to people’s demands and desires. The ongoing protests and uprisings in Iran over the years, including in December 2017 and November 2019 have shown this very clearly. Can the rights of black people be met within a system of racial apartheid? Can the rights of women be met within a system of sex apartheid? Can the unreformable be reformed?

Interestingly, Hedayat is rightly critical of a current in the West that defends the hijab as empowering and sees criticism of the veil as ‘Islamophobia’ because of cultural relativism. But wasn’t the corresponding cultural particularism of the ‘reformists’ the exact same position, albeit for different reasons? Their argument has always been that Islam and Islamic rules are ‘people’s culture,’ therefore ‘graduate change’ is needed to ‘prevent violence’ and ensure that ‘our’ culture is respected. Cultural relativism and absolutism have been the perfect positions to maintain the status quo and the Islamic system in Iran. Yet we know that culture is not homogenous or static. A defence of Islamic culture is a defence of a totalitarian state vis-à-vis the culture of dissent and resistance. In any case, if your ‘culture’ violates rights, it must be changed, condemned, abolished. You cannot legitimise violence and rights violations by saying it is ‘my culture.’ It certainly isn’t everyone’s culture. Saying so disregards the empirical evidence of diversity and the widespread opposition to Islamic rules, which are now in public view for the world to see, thanks to the Jina revolution.

Women and girls removing and burning their hijabs as the most visible manifestation of and a key pillar of Islamist rule insists on this distinction between the regime’s culture and that of free women and men. The slogan ‘Woman, Life, Freedom,’ first raised in Rojava, has shaken this regime to its very core because a theocracy that cannot control ‘its women,’ cannot continue to exist. It is via the hijab and suppression of women that the regime suppresses all of society. Hence why this is a revolution supported by all segments of society. After decades of misogynist rule, the Jina revolution proclaims: the freedom of women in any society is truly the measure of a free society. Which is why, too, that this revolution has brought to the fore the struggle against discrimination of national and sexual minorities. [As an aside, though Hedayat doesn’t see this, the hijab and sex apartheid are very much related to the maintenance of capitalism through the relegation of women to private domestic labour and reproduction.]

Whilst commendably criticising the ‘reformist’ movement, Hedayat’s worldview continues to carry its baggage. She speaks of revolution being in nature ‘dangerous and violent,’ for example. In fact, revolution is the people’s response to forty years of unrelenting violence. Revolution is the least violent means in confronting a totalitarian state. If over 600 people have been killed in protests since September 2022, if 18-20,000 people have been arrested and tortured, if hundreds have been executed since January this year alone, if over 5,000 schoolgirls have been gassed… it is the regime’s violence they are resisting, not the other way round.

Also, another open letter from Hedayat from June this year warns against ‘unrealisable utopias,’ such as ‘council rule and radical democracy.’ As Uruguayan poet and writer Eduardo Galeano says: ‘To ensure the perpetuation of the current state of affairs in lands where every minute a child dies of disease or hunger, we have to be taught to see ourselves through the eyes of the oppressor. People are trained to accept “this” order as the “natural” order and therefore as an eternal one…’

Considering direct forms of democratic rule as utopian precisely during a period of revolutionary upheaval reveals the continued ‘reformist’ point of view that can never see beyond prescribed confines and limits. More than any other time, isn’t this the time to be audacious, dream big and recognise the vast potential of the Woman, Life, Freedom revolution to fundamentally change the face of Iran and the world by establishing a more interventionist direct democracy, such as that being experimented in Rojava, which goes beyond the current old and tired ‘democracies for all’ but really for the few?

The poverty of empathy and imagination is a major obstacle to the birth of a new society in Iran as is the threat of further interventions by Western governments, the revolution’s hijacking by right-wing opposition forces like the monarchists, and most crucially the continued suppression by the Islamic regime of Iran as its only route to survival.

The Jina revolution is showing a new way, if only its call is heeded.

This article was written and will be published in Italian for Psiche in December.

Author

-

Maryam Namazie is the Spokesperson of the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain and One Law for All.

View all posts

.jpg)